A Deep Dive into Private Transactions on NEAR

Last week, we announced a collaboration with ZeroPool that will add support for private transactions to the NEAR Protocol. In NEAR today, all transactions are public—similar to Bitcoin and Ethereum. That means that—for every transaction—the sender, the receiver, and the amount transacted are all public. This is what allows everyone to audit the ledger and confirm that all the transactions are valid and no tokens are spent twice.

In many cases, it is desirable to transact in a way where only the participants involved in the transaction can have any insight into it. Achieving this while maintaining the ability to validate the correctness of the ledger is a complex task involving non-trivial cryptography.

In this blog post, I will dive deep into the internals of how private transactions will be implemented on NEAR so that no information about the participants or amounts are revealed—all without sacrificing the ability to validate the correctness.

UTXO tree

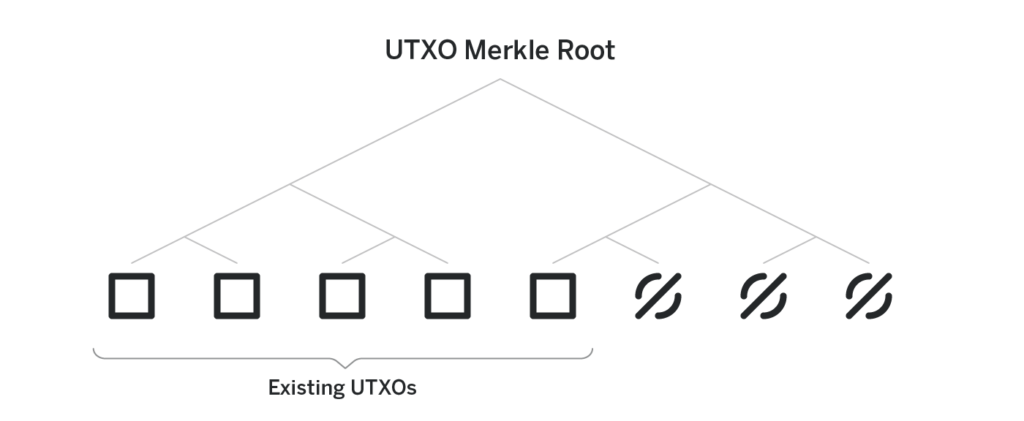

While NEAR generally uses the account model, private transactions use the unspect transaction output (UTXO) model instead. Each UTXO is a tuple (amount, receiver, salt) where amount is the amount of tokens transferred, receiver is the public key of the receiver of tokens, and salt is just some random number.

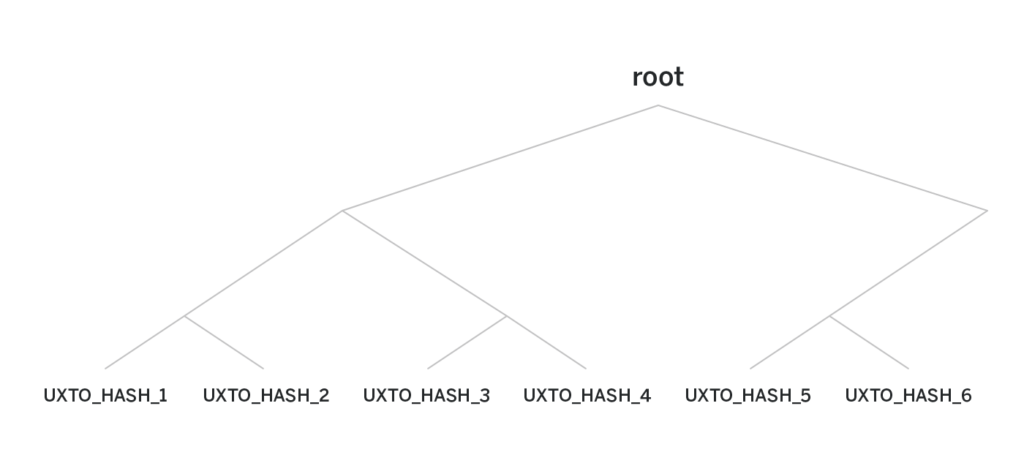

All the UTXOs are stored in a merkle tree of a predefined height. The height of the tree defines how many transactions the pool can process throughout its existence.

Each leaf of the tree is either an UTXO, or null, indicating a vacant spot that can in the future be occupied by a new UTXO. Once a spot is occupied, it never frees up. Initially, all the leaves are nulls.

The actual UTXO is never revealed to anyone but the receiver. Instead, the leaves of the merkle tree are hashes of the UTXOs—thus the need for the salt. Without the salt, if Alice knows Bob’s public key, she can brute-force different amounts and see if the hash of amount, Bob’s public key appears as the leaf of the tree, thus deanonymizing a transaction sent to Bob.

Transactions

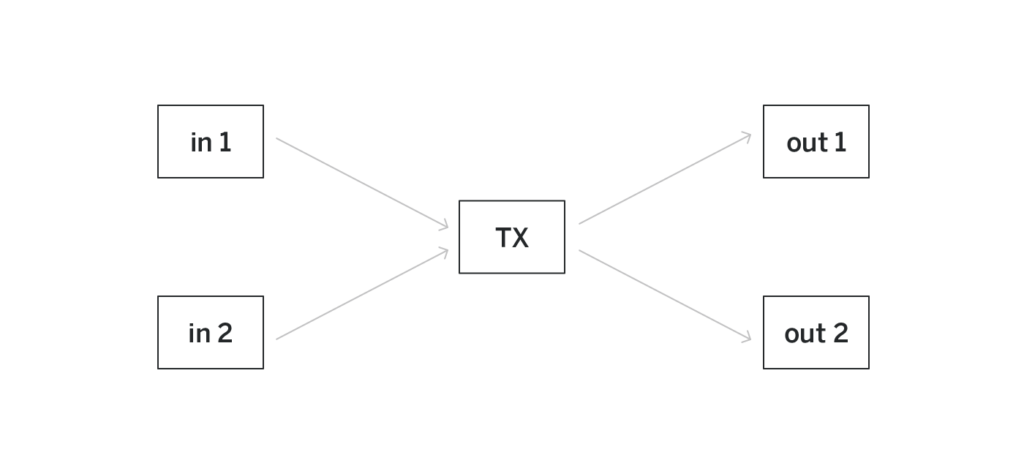

Let’s say Alice wants to send some tokens privately to Bob. The tokens that belong to Alice are those in the UTXOs in which the receiver is equal to Alice’s public key. To make a private transfer, Alice creates a transaction of the following form:

The transaction has exactly two inputs and exactly two outputs (the exact number of input and output UTXOs doesn’t have to be two but does need to be the same for all the transactions). The inputs are some existing UTXOs that correspond to some leaves of the merkle tree, and the outputs are brand-new UTXOs that will be appended to the tree.

When Alice is sending the transaction, if she actually publishes the two input UTXOs that are being spent, she will link the transaction to the transactions that produced those UTXOs. The goal of the pool is to make sure that such links cannot be established and thus the input UTXOs cannot be published.

How can we implement the transactions in such a way that the validators can confirm that it spends some existing UTXOs without revealing the actual UTXOs being spent?

ZeroPool, like many other privacy-preserving transaction engines, uses zero-knowledge succinct non-interactive arguments of knowledge (zk-SNARKs) for this purpose.

Zero-knowledge arguments of knowledge for a particular computation allow producing cryptographic proofs of the following form:

Given public input 1, public input 2 …

I know such private input 1, private input 2 …

That [some claim]

The way such arguments of knowledge work is outside the scope of this writeup. For more on this topic, this blog post provides a great overview with a lot of details.

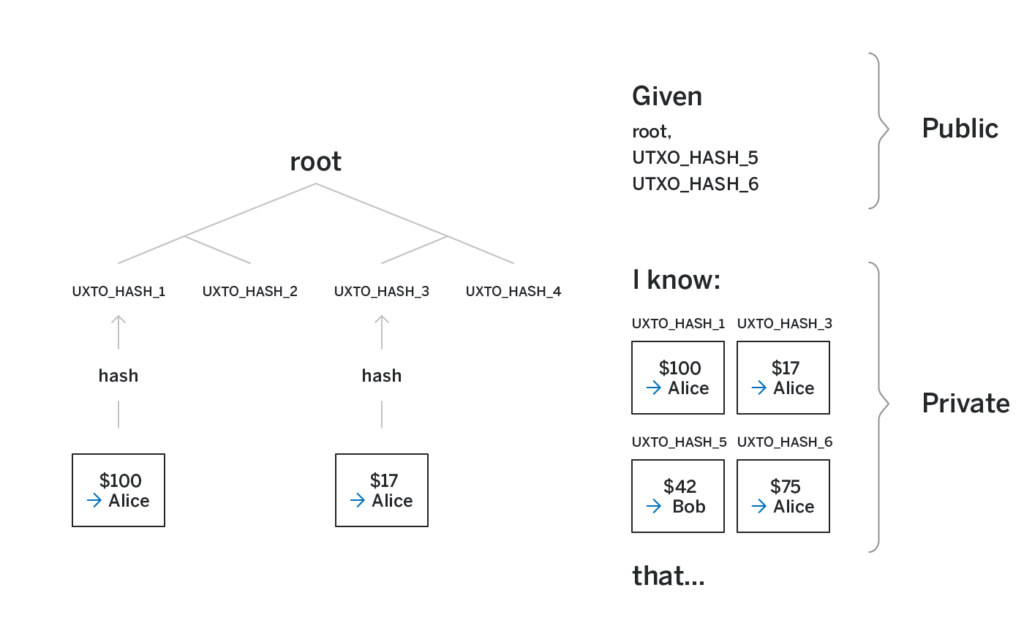

For the purposes of the private transactions, in the most naive way, the argument of knowledge can have the following form:

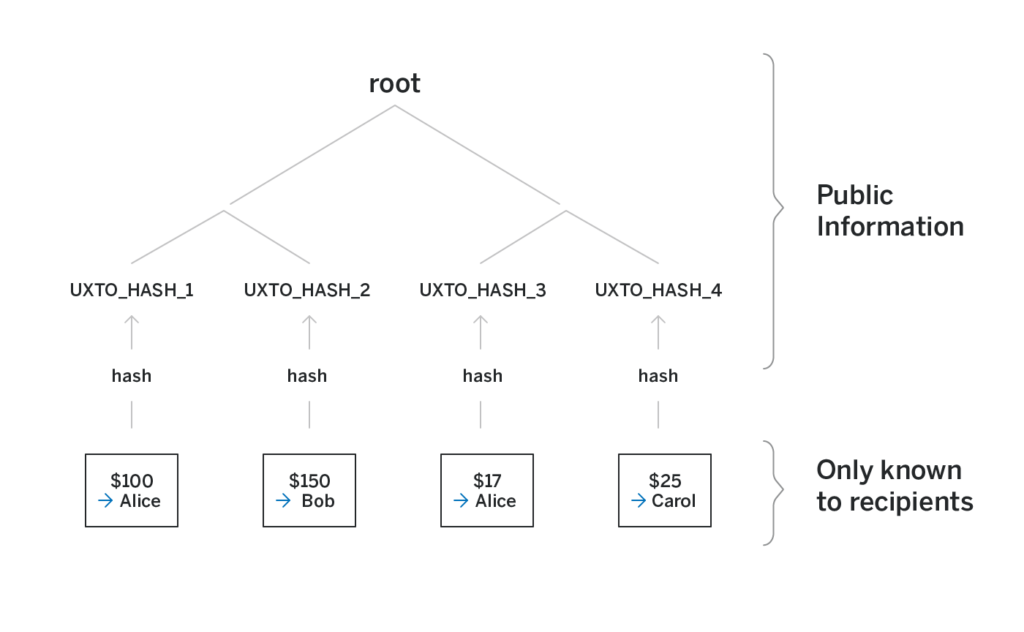

Given the merkle root, and two hashes OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2,

I know four such UTXOs IN1, IN2, OUT1, OUT2, two merkle proofs P1 and P2 and a private key x,

That hashes of OUT1 and OUT2 are correspondingly OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2, and the receiver in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the public key X that corresponds to x, and the merkle proofs P1 and P2 are valid proofs of inclusion of IN1 and IN2 in a tree with the given merkle root, and the sum of amounts in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the sum of amounts in OUT1 and OUT2.

The transaction then consists of merkle_root, out_hash1, out_hash2, argument of knowledge, and nothing in the transaction reveals the recipients of the output UTXOs nor links the output UTXOs to the particular input UTXOs. Moreover, even the amount transacted is not revealed in the transaction.

For example, in the figure above, say the first and third UTXOs in the merkle tree have Alice as the recipient and amounts of $100 and $17 correspondingly. Alice knows those two UTXOs but has no insight into any other UTXO in the tree. If she wants to send $42 to Bob, she creates a transaction that uses both of her UTXOs as inputs and creates two new outputs: one sending $42 to Bob and another sending the remaining $75 to herself. She reveals the UTXO that is intended for Bob to Bob. But the remaining UTXOs are not known to anyone but her. Moreover, even the hashes of the input UTXOs are not revealed to anyone.

The smart contract that maintains the pool, once it receives such a transaction, verifies the argument of knowledge. If it checks out, it appends the two new UTXOs to the tree:

Once Bob receives the UTXO from Alice, he waits until the hash of the UTXO appears in the tree. Once it does, Bob has the tokens.

The problem with this naive approach is that the same input UTXO can be spent twice. Since nobody but Alice knows the hashes of the input UTXOs, the pool cannot remove the spent UTXOs from the merkle tree because it doesn’t know what to remove to begin with.

If Alice creates two different zero-knowledge arguments that both spend the same two inputs, everybody will be able to verify that both transactions spend some UTXOs existing in the merkle tree but will have no insight into the fact that those UTXOs are the same in the two transactions.

To address this problem, we add a concept of a nullifier. In the simplest form for a particular UTXO the nullifier is a hash of the UTXO and the private key of the receiver of that UTXO. We then change the argument of knowledge for the transaction to the following:

Given the merkle root, and two hashes OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2, and two more hashes NULLIFIER1 and NULLIFIER2

I know four such UTXOs IN1, IN2, OUT1, OUT2, two merkle proofs P1 and P2 and a private key x,

That hashes of OUT1 and OUT2 are correspondingly OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2, and the receiver in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the public key X that corresponds to x, and the merkle proofs P1 and P2 are valid proofs of inclusion of IN1 and IN2 in a tree with the given merkle root, and the sum of amounts in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the sum of amounts in OUT1 and OUT2, and hash (IN1, x) is equal to NULLIFIER1 and hash (IN2, x) is equal to NULLIFIER2

Note that any transaction that spends a particular UTXO will have the same NULLIFIER computed because the NULLIFIER only depends on the hash of the UTXO and the private key that uniquely corresponds to the public key in the UTXO. And since the NULLIFIER in the argument of knowledge above is in the “Given” clause, which is public, if two transactions that spend the same UTXO are ever published, everybody will be able to observe that they have the same NULLIFIER and discard the later of the two transactions.

Also note that, for as long as the hash used to compute it is preimage resistant, the NULLIFIER reveals nothing about either the input UTXO or the private key of the receiver.

Depositing, Withdrawing

The transactions described above work great to move assets within the pool. But for the pool to be of any use, there must be a way to move assets from outside the pool into the pool and from the pool back outside of it.

To that extent, the private transaction format is extended to have an extra field called delta, such that the sum of the amounts in input UTXOs is equal to the sum of the amounts in the output UTXOs plus delta:

Given the merkle root, and two hashes OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2, two more hashes NULLIFIER1 and NULLIFIER2 and a value delta

I know four such UTXOs IN1, IN2, OUT1, OUT2, two merkle proofs P1 and P2 and a private key x,

That hashes of OUT1 and OUT2 are correspondingly OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2, and the receiver in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the public key X that corresponds to x, and the merkle proofs P1 and P2 are valid proofs of inclusion of IN1 and IN2 in a tree with the given merkle root, and the sum of amounts in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the sum of amounts in OUT1 and OUT2 plus delta, and hash (IN1, x) is equal to NULLIFIER1 and hash (IN2, x) is equal to NULLIFIER2

Note that the delta is in the given clause and is thus public.

When such a transaction is processed on NEAR, if the delta is negative (i.e., so that more tokens enter the private transaction than exit it), the extra tokens are deposited to the sender’s account. If the delta is positive (i.e., more tokens exit the transaction than enter it), such a transaction is only valid if the remaining tokens are attached to it.

Transaction fees

Private transactions do not allow linking between the newly created UTXOs and the UTXOs that were used as inputs. However, for any transaction to be included on the NEAR chain, the transaction sender must pay for gas and thus must have native NEAR tokens in the sending account. Those tokens somehow got to that account, which creates linkability and largely defeats the purpose of the private transactions.

To address the problem, we introduce a new role in the system called relayer.

Say Alice wants to send a transaction to Bob and wants to use Ryan as the relayer. The gas fee for the transaction is less than Ⓝ1 and Alice is willing to pay Ryan Ⓝ1 for submitting the transaction to the chain.

Alice, who might not have an account on NEAR at all, creates a private transaction in which the sum of the two input UTXO amounts is Ⓝ1 less than the sum of the output UTXO amounts. The remaining Ⓝ1 is withdrawn to the account of the submitter of the transaction. Ryan collects the transaction from Alice, confirms the validity of the transaction, and submits it from his account, spending less than Ⓝ1 in gas but receiving Ⓝ1 as the result of the transaction.

Alice ends up submitting the transaction without revealing herself and Ryan receives a small payout. Note that no party needs to trust the other in this interaction: Ryan cannot tamper with the transaction in any way and thus can only either submit it or do nothing. So, the biggest risk for Alice is the possibility that her transaction is not submitted (in which case she can ask another relayer to submit it). Ryan verifies the transaction before submitting it and thus doesn’t risk spending gas and not receiving his payment unless another relayer front ran them.

Further improvements

The model described so far is a fully functional pool for private transactions. In this section, I will briefly mention several other aspects that improve the security or usability of the pool:

Discovering payments

When describing the transactions above, I mentioned that when Alice sends tokens privately to Bob, she shares the newly created UTXO with him. This requires Alice communicating with Bob off-chain, which is undesirable. Instead, the pool can be extended to store all the UTXOs encrypted with the public keys of their recipients. When Alice sends money to Bob and creates two new UTXOs, she encrypts the UTXO that has Bob as the recipient with Bob’s public key.

On his end, Bob monitors all the newly created UTXOs and tries to decrypt each one with his private key. Once he gets to the UTXO created by Alice, the decryption succeeds, and Bob discovers their UTXO using exclusively on-chain communication.

Decoupling signing and proving

When Alice creates a transaction, she needs to create a complex proof that in particular uses the knowledge of her private key. Thus, the machine that computes the proof needs access to the private key, which is undesirable.

Generally, it is preferable to have the private keys on some external hardware device that only has limited functionality, such as signing messages. Computing arguments of knowledge is generally way outside the capabilities of such hardware devices.

To accommodate these devices, we make the key generation create three keys instead of two:

Private Key, Decryption Key, Public Key

Here, a message encrypted with the Public Key can be decrypted with the Decryption Key. Similarly, a signature created with the Private Key can be verified having access to the Decryption Key. Only the public key is revealed publicly. The decryption key is stored on the device that computes transaction proofs and the private key is stored on the external device that can only sign messages.

We can then alter the argument of knowledge in the following way:

Given the merkle root, and two hashes OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2, and two more hashes NULLIFIER1 and NULLIFIER2

I know four such UTXOs IN1, IN2, OUT1, OUT2, two merkle proofs P1 and P2, a decryption key d and a signature s,

That hashes of OUT1 and OUT2 are correspondingly OUT_HASH1 and OUT_HASH2, and the receiver in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the public key X that corresponds to d, and the merkle proofs P1 and P2 are valid proofs of inclusion of IN1 and IN2 in a tree with the given merkle root, and the sum of amounts in IN1 and IN2 is equal to the sum of amounts in OUT1 and OUT2, and hash (IN1, d) is equal to NULLIFIER1 and hash (IN2, d) is equal to NULLIFIER2, and s is a signature on a message (IN1, IN2, OUT1, OUT2) that is valid against d

When Alice then wants to create a transaction, she uses the hardware device to sign (IN1, IN2, OUT1, OUT2). She then uses the signature s to generate the proof on the machine that only has access to the decryption key.

Note that without access to the hardware device one cannot generate s and thus cannot spend money—even if they get access to the machine that is used for proving.

Supporting more tokens

The private transactions are not limited to the native NEAR tokens. With a very slight modification, the pool can be generalized to support any tokens using the same anonymity pool for all of them. The exact construction is outside the scope of this write-up, however.

Outro

Besides collaborating with NEAR, ZeroPool also builds private transactions for Ethereum and is primarily funded by the community. Consider supporting them on Gitcoin.

Educational Materials

This write-up is part of an ongoing effort to create high-quality educational materials about blockchain protocols. Check out this video series in which we dive deep into the design of various protocols—such as Ethereum, Cosmos, Polkadot, and others—as well as our other technical write-ups.

Supporting Early Stage Blockchain Companies

If you are an entrepreneur in the web3 space, consider joining our accelerator with mentors from tier1 companies and investment firms in the space: http://openwebcollective.com/. We help with all the aspects of building the business, including identifying the market, business development, marketing, and fundraising.

Stay in Touch

We are NEAR, an open source sharded blockchain protocol. You can deploy your first fully functional decentralized application to NEAR within minutes from our fully functional web-based IDE.

Follow us on Twitter to get updates about our new educational materials, while keeping tabs on our progress toward the decentralized future.

Share this:

Join the community:

Follow NEAR:

More posts from our blog